By our time-travelling contributor Andy Frombolton

The competition for the right to play Australia in the 2023 T20 World Cup Final went pretty much as predicted.

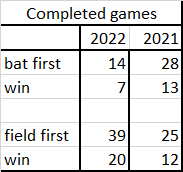

Most of the teams enjoyed some pre-tournament practice; although the quality varied significantly and didn’t test the stronger teams. England came into the series having defeated Hayley Matthews before Christmas, whilst NZ similarly dispatched Bangladesh; Australia saw off Pakistan and most recently South Africa played West Indies and India. The results of these various series seemed to merely confirm the obvious power hierarchy with the losing opposition probably gaining far more from these games than the largely-untested victors. Again, nothing in the friendlies or the warm-up games alluded to a shifting in the rankings and provided little scope for experimentation. As with all the various pre-tournament series, it was disappointing how often the weaker teams (whether by their choice or insertion) batted first in these games; meaning many batters started the tournament seriously short of match practice.

Beyond the actual results, observers may perhaps look back at this tournament for 3 reasons.

Firstly, it constituted the moment when (hopefully) the administrators of Australian, English and Indian women’s cricket finally realised that it’s not much fun (nor is it helpful for the development of the international game) playing countries who simply aren’t very good and, more to the point, which have little prospect of becoming much better in the near future unless ‘The Big 3’ seize the initiative to help them improve by funding player exchanges, loaning them coaches and giving them lots of quality match practice . including low key series against development squads. There were far too many mismatches – to the point where some opined that, having so long sought a wider audience for the women’s game, this tournament may have done as much harm as good with many fans left disappointed at the standard of cricket and the cynics feeling validated.

Secondly, it was also the last tournament played before the advent of the WIPL when the whole world was to change for a small number of players. With the potential for life-changing amounts to be earned, it was perhaps inevitable that this impacted some performances; often imperceptibly, always unconsciously. But who could blame a player in possible contention for a WIPL contract for not throwing themselves quite so vigorously around on the boundary to save a couple of runs (with the resultant risk of injury) if the result was not going to be impacted or if a batter chasing a low target was possibly more focussed on scoring runs for themselves than taking risks to win the game early? Some even suggested (without any proof) that this was why, contra to previous tournaments, so many of the major teams elected to bat first because inserting the opposition and dismissing them for a low score wouldn’t leave much opportunity for batters to impress the WIPL selectors.

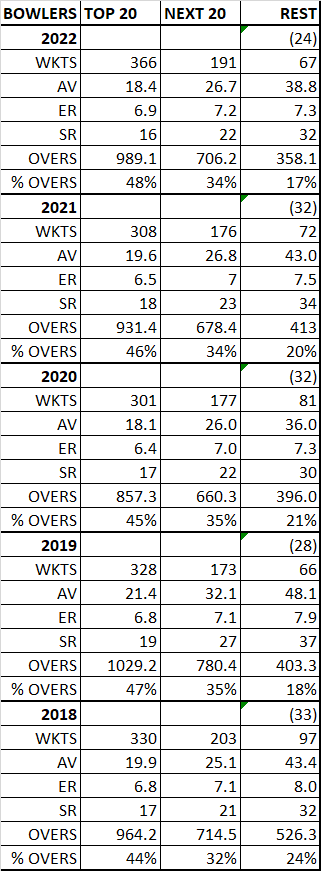

Thirdly, there was a significant shift in the level of analysis and scrutiny which performances were subject to. Suddenly, there was a lot more data available and opposition teams were using it – with the consequence that life suddenly became much harder for many players. The truly good players serenely carried on being very good, but many others were found out. Who knew Player X simply couldn’t score once you cut off her 2 best shots? Now, every batter knows that bowler Y changes their run-up when they bowl their googly (and that it’s usually short). And “there’s always 2 to Player Z” because they have a weak throw. More was expected of players generically, in respect of general athleticism and skills, and the commentators were more willing to call out any instances which fell beneath the new higher benchmarks. Many players relished the chance to showcase their skills, but not all coped well under the new regime.

The group stages went very much as expected – a series of mismatched games between the Big 5 and the rest. (Or, to better recognise the relative status of the teams, … “between ‘The Big 1’, ‘The Next 2’, and ‘Numbers 4 and 5‘ and the rest”.) The other teams played with conviction, spirit and enjoyed moments which hinted at their potential, but unfortunately many games didn’t make for riveting viewing.

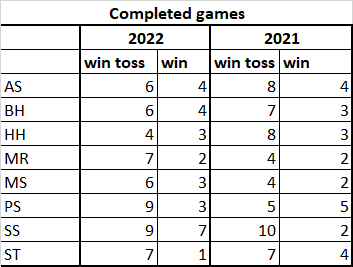

In Group A there was the question of whether South Africa or New Zealand would take second place; a question answered in their head-to-head when the Kiwis, several of their veterans seemingly inspired by the prospect of what might possibly be their last outing on the world stage, dispatched a spirited South African team desperately missing DvN’s captaincy nous, lacking the necessary spinning options and missing the batting power to chase down NZ’s impressive total built on the back of Devine’s brutal 80 at a SR of 150. In the wooden spoon game Bangladesh thrashed Sri Lanka to underpin how far standards have fallen there (and also how much Bangladesh had improved).

In Group B, whilst there was never any real doubt which teams would take the top 2 slots, both India and England still managed those moments of fallibility which so exasperates fans and commentators alike. Playing their first 2 games at Boland Park, several England batters took advantage of the ball travelling further in the thin air to clear the ropes, albeit against inexperienced and variable bowling attacks. Neither game did much to prepare the team for the challenges of facing a more skilful Indian attack.

India meanwhile ruthlessly dispatched Pakistan and West Indies, their batters similarly taking advantage of the small boundaries and poor fielding.

Come the India v England match at Gqeberha (formerly Port Elisabeth), England fielded a batting-heavy team, won the toss, chose to bat first and swiftly found themselves reduced to 25-4; three of the batters failing to clear the ropes at sea level as they’d done at Boland Park. It took some slow but skilful rebuilding by the middle order and some late bludgeoning by K Sciver-Brunt and Ecclestone to get England to what still looked like a severely below-par score. However, as everyone knows, it’s bowling attacks which win T20s, not batters, and fortunately all England’s bowlers utilised the conditions well with Amy Jones standing up to the stumps to everyone, inducing first frustration and then mistakes from Mandhana and Kaur. England scraped home by 8 runs.

England being England, they then nearly made a complete mess of chasing 110 in their final group match against Pakistan but still ended atop of Group B.

The 2 semi-finals – as is so often the case in global tournaments – constituted the best 2 games of the whole tournament.

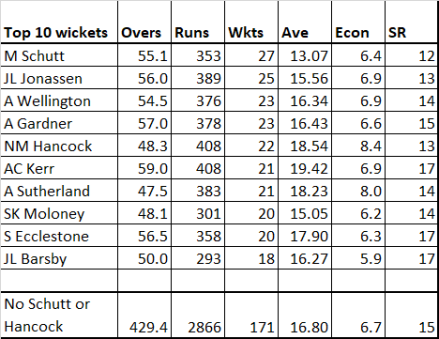

England versus NZ was a probably the best game of all. The 2 teams had already met recently in 3 friendlies and 1 warm up, so each knew everything about the other’s strengths and weaknesses. With Knight forced to sit the game out following some inflammation to her hip, England found themselves unexpectedly captained, not by official vice captain Sciver-Brunt, but by Ecclestone – coach Jon Lewis demonstrating his willingness to move on from the previous regime. Denied their preference to bat first, England deployed surprise tactics and opened with spin at both ends and at the end of the powerplay NZ were just 30-2 with Bates and Kerr both back in the dugout. Excited pundits urged England to press home their advantage given NZ’s lack of batting depth, using Dunkley’s occasional part-time spin if necessary, but rather than continue with what had worked, Ecclestone seemed to lose her confidence in the tactic and brought on N. Sciver-Brunt and Bell in the middle overs. Pace on the ball was what Green and Devine had wanted with the small outfield and the following 10 overs was carnage as NZ reached 120-3 off 16. A couple of missed half-chances and some targeting of England’s 5th / 6th bowlers didn’t help and 150 or even 160 looked a distinct possibility. However, the (with hindsight) inspired decision to deploy the rarely-used Danni Wyatt to bowl the 17th over saw 2 wickets fall and Ecclestone and Cross closed out the innings with tight bowling which was too good for the NZ middle order.

141 was still a tough target though and things looked bleak when England lost 2 wickets in the first 3 overs (Wyatt again caught on the boundary and Capsey not making it home for a sharp second run). Thereafter Dunkley and N. Sciver-Brunt settled the nerves and kept up with the run rate until the 14th over whereafter 4 wickets fell for just 7 runs and it took Dean, seizing her chance in Knight’s absence, to smash 18 off 5 balls and see England home with 1 ball to spare.

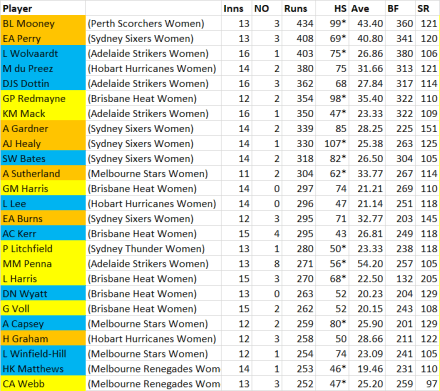

In the other semi-final, India provided Australia with a huge scare. 3 wickets in the powerplay saw Australia’s middle order – so rarely tested in the past 2 years – required to deliver. Watched on by Grace Harris, cursed to have been born in the only country where she and her sister wouldn’t be permanent fixtures in the national squad, Mooney, Perry and Gardener delivered a masterclass in manoeuvring the bowling and sharp running. Australia’s 172-5 looked formidable, but fans who’d watched Australia’s pre-Christmas tour where India had twice scored more than 180 batting second knew that this Indian team wouldn’t think this total was beyond them especially if the Madhana-Kaur show came to town.

After 6 overs, India’s score stood at 72-0. Australia had already used 5 bowlers and looked bereft of ideas. They’d used 9 bowlers in the 3rd T20 against Pakistan and similarly-desperate tactics looked on the cards. However, as if written in the stars, Healey then took an incredible diving catch down the left to dimiss Mandhana, a riposte to those arguing that Mooney should have the gloves to make space for Harris, and thereafter Australia wrestled back control; India falling just 4 short when, after 2 warnings, Brown ran out Sharma for backing up too far off the final ball. (The English media loved this moment, accompanying the photo with the sub-editor’s witty caption ‘Karma for Sharma’.)

The Final saw Knight fit again and another sign that she and Jon Lewis were willing to make tough decisions with the dropping of Amy Jones whose keeping hadn’t been to her very-high standards for much of the tournament (which had seemingly impacted her confidence and thus her contributions with the bat ). Awarding the gloves to Winfield-Hill was the right decision for the moment and Jon Lewis tactfully declined to comment on anything to do with central contracts awarded before his appointment.

England won the toss and, having noted how the pitches got easier to play on in the SA20 as the day wore on, elected to field even though this would require them to chase, something they’d tended to avoid whenever possible in the previous few years.

Returning captain Knight chose not to replicate Ecclestone’s successful run-stifling-spin tactics and the openers started as Australia meant to go. 5 boundaries came from the first 2 overs – and no dot balls. Mooney (the ‘best player in the world’ if stats took proper account of fielding contributions) and Healey quickly induced several pieces of ragged fielding by alternating ‘walloping the ball’ with ‘tip and run’ and it took a great piece of fielding by Bouchier to run out Mooney. Luckily, England had picked 3 spinners for the final and this trio of England spinners, complemented by the routinely-(self)-under-deployed Knight, wrestled back a degree of control.

Still at the half way stage 167-6 looked a very good score on a wicket demonstrating variable bounce, and so it transpired to be.

168 equates to a SR of 140 and unfortunately England have only 1 batter with a proven ability to strike above 120 – Wyatt. To Wyatt, Brown came round the wicket, bowling full on her pads with the 6-3 offside field denied her any value for her shots again and again. For the other batters, Lanning revealed her ‘mind games’ masterstroke, bringing every fielder except 1 inside the inner circle to create a sneering ring of encroaching fielders. Denied the opportunity to take sharp singles and not able to go over the ring, runs dried up. After 10 overs, England were just 49-4; two skied shots, a terrible mix-up and a stumping (some maintained it should have been deemed ‘a run-out’ so far was the desperate batter down the wicket) accounting for the wickets. With the run rate over 12, the outcome was already decided but Lanning went for the kill bowling King and Gardner for 8 straight overs in tandem. The end, when it came, saw England all out for 112 with in the 18th over.

Australia thus retained the T20 world cup for the third time in a row whilst the 2nd, 3rd and 4th places broadly confirmed what everyone knew before the competition started. Australia are deserved and indisputable world champions (and their A side would have a good chance of being #2), India has leapt above England to warrant the #2 position, England are a potent side but lacking batting firepower, whilst South Africa and NZ have both peaked (for now).

So, ‘Well played Australia’, well done England and ‘Look out, world!’ for India’s star is in the ascendancy.